Somewhere inside a forgotten room in Hyderabad, a crow with the hood of a cobra waits. Not a living creature, but a riveting brass totem with a story so rich, it can take hours to tell. Around it lie ghostly wind instruments made of hide and bone, leather bags that breathe music, and shadowy relics from India’s ancient forest tribes.

These are not just objects; they are echoes of long-lost worlds. And now, these artefacts, many of which once mimicked the wind, birds and rain, are in search of a home — a home in Hyderabad bordering the deep jungles and forest tract of central India, where these instruments were first born from ingenuity, ritual, and breath.

These have journeyed far to get here, collected over five decades by one man obsessed with memory and history: ethnographer Jayadheer Tirumala Rao.

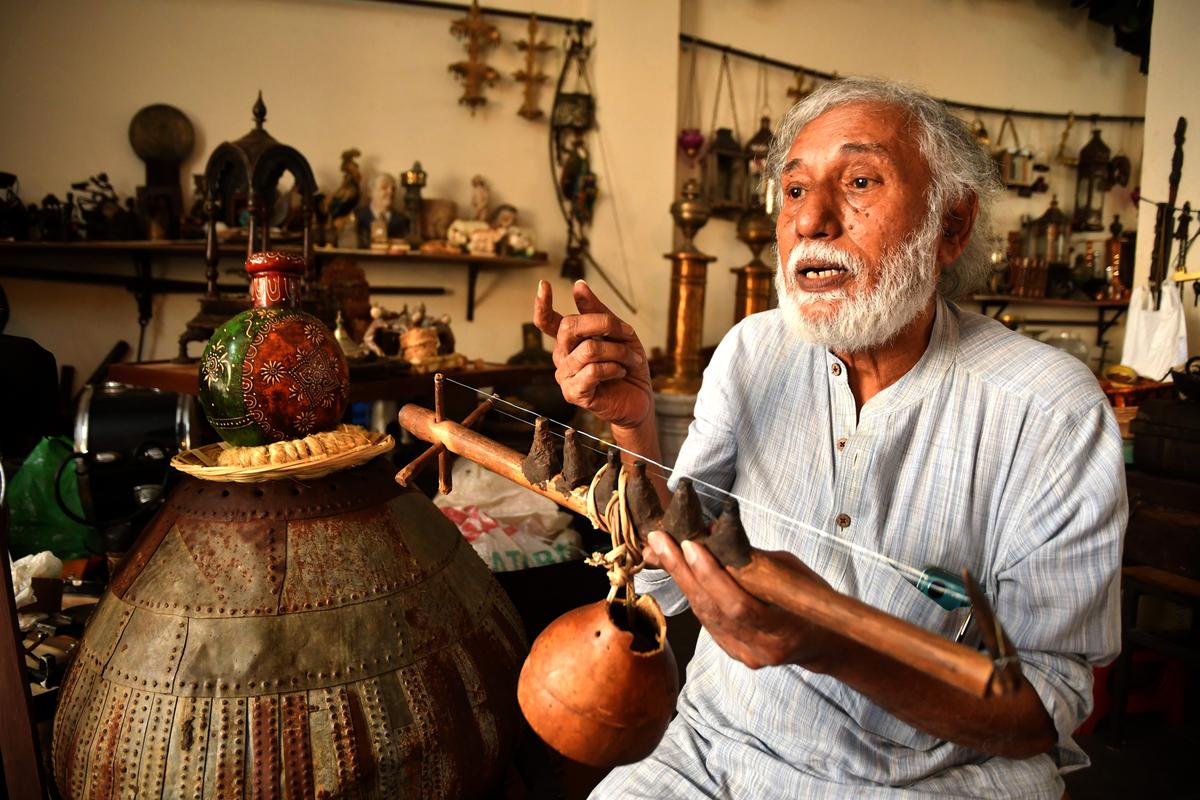

His treasure trove lies scattered across six rooms tucked deep within the Telugu University campus in Nampally. Here, between sunlit corridors and dusty alcoves, Rao moves like a man among old friends. The wide courtyard is littered with weathered cartwheels, carved doors, door frames, totem poles and what looks like a sculptor’s madness — but each piece has its own story.

“This is a hanging inkpot made with brass,” the 75-year-old says, lifting a crouched, bull-shaped vessel with a hidden cap for dipping ink. “It was a gift from a student while I was teaching in Hanamkonda.” There are 200 known varieties of hanging inkpots among Adivasi communities, and Rao has managed to collect 40 of them.

The collector and his calling

It all began half a century ago in Warangal district of Telangana, when a young postgraduate student was nudged away from academia by his mentor, folklorist B.Ramaraju, and asked to take the tougher road — field work. Rao took off, hitchhiking, riding rickety buses and walking for miles through Telangana’s interior in the mid-1970s, when roads were few and forests many.

“I travelled by train, I travelled by bus. I mostly walked, as there were hardly any buses in 1975, to research and understand folk and Adivasi culture. I began collecting musical instruments that did not work,” he recalls, sitting among his archive. “Once, I started walking from Charla in Bhadrachalam in the morning and by 8 p.m., I realised I was lost. I walked all night and somehow ended up at the same point I had started from. That was scary.”

Gradually, however, those walks bore fruit. Rao’s first acquisition was the ‘Jamadika’in the 1970s— a haunting stringed instrument enclosed in a drum, played only by a sub-clan of the Madiga community. As he documented folk ballads and songs of the Telangana Peasant Rebellion (Rythuangu Poratam) and folk literature, Rao also began collecting objects from the communities he visited — musical relics, domestic tools and even pieces of performance history.

One evening, during a visit to the Saradlu community about 30 kilometres from Kolanupaka, a village in Yadadri Bhuvanagiri district, he stayed back to listen to folk songs of the Telangana Armed Rebellion. The men invited him along for a hunt. That night, his dinner was roast garden lizards. “That was it. That was my meal,” he says with a shrug.

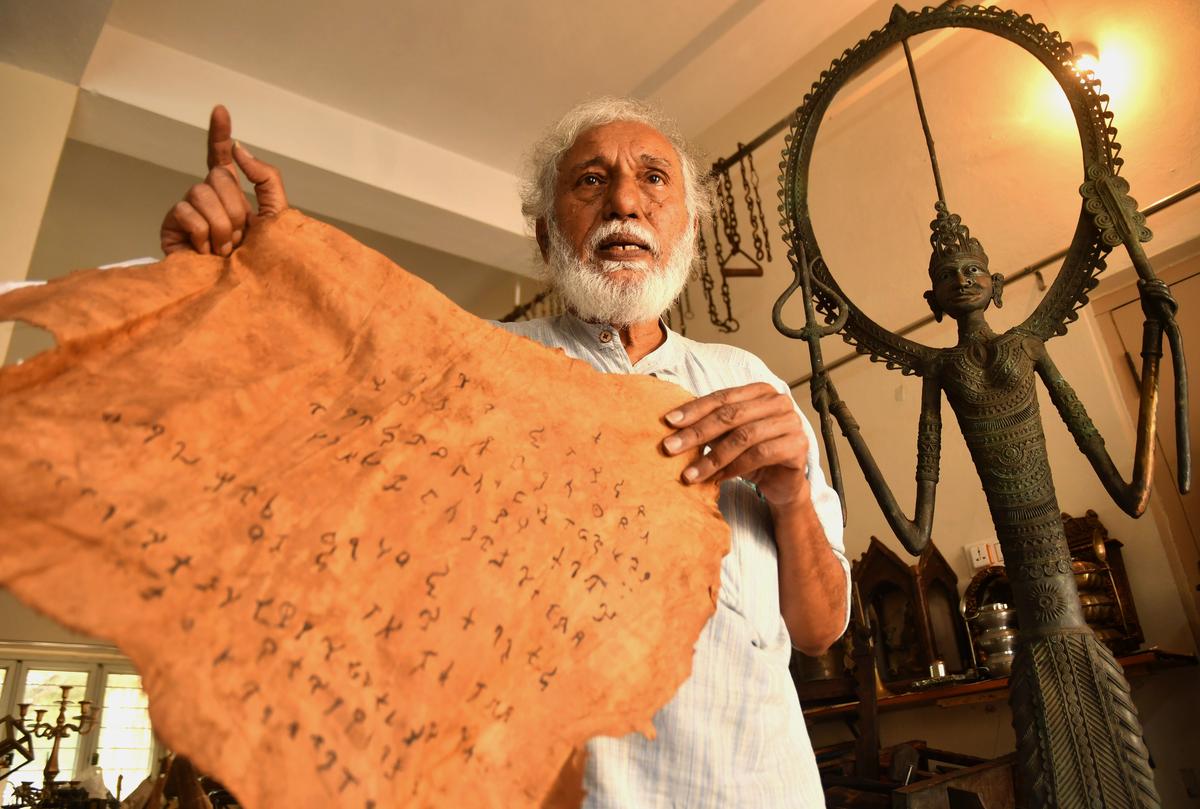

Then he holds up a brass object that looks like a bird. “This is a crow with a snake hood in the middle. It is a totemic object for a clan, called Kaki Padagala Varu. They keep it close during a performance of the Mahabharata, that may last for three days with music and old manuscripts,” shares Rao.

Part of his collection is the ‘Thitthi’,a leather bag attached to a bamboo pipe used by a community called Kommuluvaru that hums like an ancestral bagpipe. And the rare ‘Bruhat Kinnera’ with 13 steps and three gourds, an instrument even older than the veena.

“Very few are gifts. Most of them have been purchased,” says Rao’s wife, R.Neela, a homemaker who has shouldered the endless task of cleaning and caring for this vast, uncatalogued collection.

The instruments and artefacts — totemic objects, musical devices, writing tools, masks, flags, household pieces — lie undocumented, without labels or timelines or the gentle touch of a museologist, in these six rooms of the Telugu University. Yet, they hold within them the pulse of India’s earliest communities — the Gonds, Saradlu, Totis, Koyas, Gutti Koyas, Pradhans, Mauryas, Chenchus, Lambadis, and the clans of Manda Hechu, Bolla Pujari, Tera Chiralavaru Daccali, Chindu, Mastidu, Runjavaru and Maladasari. These communities, whose homelands once lay deep in the forested heart of central India, are now vanishing along with their cultures.

Struggle for shelter

Over a century ago, Osmania University (OU) rose from a 2,500-acre expanse that once belonged to one of the courtesans of the Nizam of Hyderabad. It became the first university in India to adopt Urdu as its medium of instruction, and its campus, dotted with ancient stepwells and serais, has since become more than just a seat of higher learning. It has been a crucible of protest, its student movements playing a pivotal role in the birth of Telangana in June 2014.

It was here, amid this charged legacy of scholarship and dissent, that Rao’s long-wandering museum collection was finally offered a space to rest. After decades of being crammed into scattered rooms in Telugu University, two disused bungalows nestled in a quiet, leafy quadrangle off the main road of OU were allocated for the museum. The move came with the backing of Telangana Chief Minister, A.Revanth Reddy.

But the students of OU have other plans.

Construction work under way for a cultural museum on Osmania University campus in Hyderabad which were halted following student protests.

| Photo Credit:

Nagara Gopal

“The land where the museum is set to be established is OU land. It cannot be leased out to private individuals. The university used to have 2,500 acres. Now, it has shrunk to 1,300 acres. Once land is leased, the university never regains control,” says Druhan, president of the OU unit of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), who is spearheading the protests against the establishment.

Tensions escalated quickly. Work on the two bungalows came to a sudden halt after student leaders reportedly threatened the labourers and contractors at the site. They left in haste. The buildings now lie silent once again, caught in the crossfire between heritage and protest.

“Why involve private parties at all,” asks Raju, another ABVP leader from the university. “OU can run such a museum itself. Even Union Minister G. Kishan Reddy had once promised ₹10 crore for a museum, but that proposal was never taken up.”

Land within the university has long been a bone of contention, with student unions seeing themselves as its vigilant custodians. Over the years, various encroachments — some with questionable legitimacy, others with official paperwork — have eaten into the once-sprawling campus. And for student leaders, every new construction represents another line of defense to hold.

Back in 1994, a one-man commission led by Justice O.Chinnappa Reddy drew a firm red line around OU land.

After reviewing years of land dealings, his report cited a crucial resolution passed by the University’s Syndicate as far back as December 26, 1986. It read with finality: “There was a firm resolution of the Syndicate of the Osmania University, totally abandoning the practice of allotting University lands to outside agencies for whatever purpose, educational research or otherwise.” In essence, the university had resolved to shut the door, permanently, on all outside claims to its land.

Living culture, not just curios

But the question at the heart of the current standoff is this: can an archive of folk memory, painstakingly gathered over half a century, be seen as just another “outside agency”?

“This isn’t a private collection to be locked up in a shelf at home,” says journalist Ramachandra Murthy, one of the earliest and most vocal supporters of Rao’s mission.

“These cultural objects have travelled as far as Paris, were once displayed at the Rashtrapati Nilayam, and even spent time in the State Gallery of Art. They are not museum curios for personal gratification; they are pieces of living culture. This kind of collection cannot be managed by an individual. It needs institutional support,” says Murthy.

Many in the academic world agree. “The students protesting have been misled,” M.Kodandaram, former professor and civil society activist, had been quoted as saying. “This collection could be of immense value to researchers working on tribal life, history, anthropology and music. It is not just about artefacts; it is about Telangana’s cultural history.”

Hyderabad, after all, is no stranger to personal collections becoming public legacies. It is home to perhaps the biggest cache of cultural artefacts acquired by one person — Salar Jung. These objects were the genesis of the Salar Jung Museum, one of India’s largest and most visited institutions of national importance.

Tucked into a quiet bylane of Domalguda is another legacy: the Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art, with its enviable spread of miniature paintings and manuscripts, a quiet cultural gem of the city.

Rao’s journey, however, has been less institutional and far more intimate. He recalls an early turning point, nearly four decades ago, when the full weight of his collection first dawned on him. “I was shifting houses in Chikkadpally area [of Hyderabad]. I had booked a small vehicle for three trips. But as the workers started hauling things down from the attic, they kept discovering more and more. Eventually, they got frustrated and demanded extra money. That is when I realised, this collection had grown larger than I imagined,” he reminisces.

Now, nearly 40 years later, Rao stands at another crossroads. His collection, born of long treks through forests, folk memory and fading oral traditions has once again outgrown its shelter. Will it finally find a permanent home within OU’s storied grounds? Or will the struggle to shelter India’s sonic and cultural past continue, one room — and one protest — at a time?

Published – June 06, 2025 08:05 am IST